QA10: Justin Fanelli, Acting CTO of the Navy, on his wishlist, if Silicon Valley is building the right stuff, and how to create a cross-country innovation community

Hacking for Peace and Security

Justin Fanelli wears a number of different hats. An Associate Professor at Georgetown University, he also plays a critical role for the U.S. Navy leading their technology acquisition and deployment efforts across the entire organization.

Atoms & Bits caught up with Justin after he appeared at Playground’s Annual General Meeting earlier this year. Our conversation covered topics like how to design successful teams, the best way to build in the national interest, and where the U.S. innovation ecosystem may be headed next.

A&B: Tell us about your current position and what it entails.

Justin Fanelli: The longest title I have is Technical Director at Program Executive Office Digital and Enterprise Services, or “TD at PEO Digital.” I am also Acting CTO at the U.S. Department of the Navy. I still support the ARPA-H mission as they have moved from a startup agency to a dream team working to improve American healthcare in a big way. PEO is DoD acquisition. We manage a stack of portfolios that does billions of dollars of work on network and cloud infrastructure, cyber, endpoint devices, and enabling at the enterprise level. It is more buying than anything else. But it is also design, architecture, and smart integration. It’s an execution job. The CTO job has broader strategy and policy aspects. As you may have guessed, these two roles are not often held by the same person with the same teams. In this particular case, I’ve gotten to do both for the last year and a half and we’ve derived benefits from the two teams interacting so closely.

A&B: How do you manage both of those positions?

Justin Fanelli: As often as we can, those two teams “shake and bake” collectively. We have a Secretary, a CNO, and a CIO with vision and a lot of top cover to execute differently for outcomes overmatch. We wanted to use that to blow past the status quo. We’ve written a manifesto to do strategy-to-execution differently and better as a part of our public-private partnership. Then we updated the manifesto to “strategy through execution.” It’s about as fast as I’ve seen good quality work in the form of outcomes and motivated teams anywhere. Other than operational surges during really critical times or out in theater, this is one of the best sustained efforts that I’ve seen. That’s a credit to everyone who’s involved — the existing partners who have upped their game, all the new companies we’ve brought in, and government superstars who could work anywhere in the world.

A&B: And who do these teams serve?

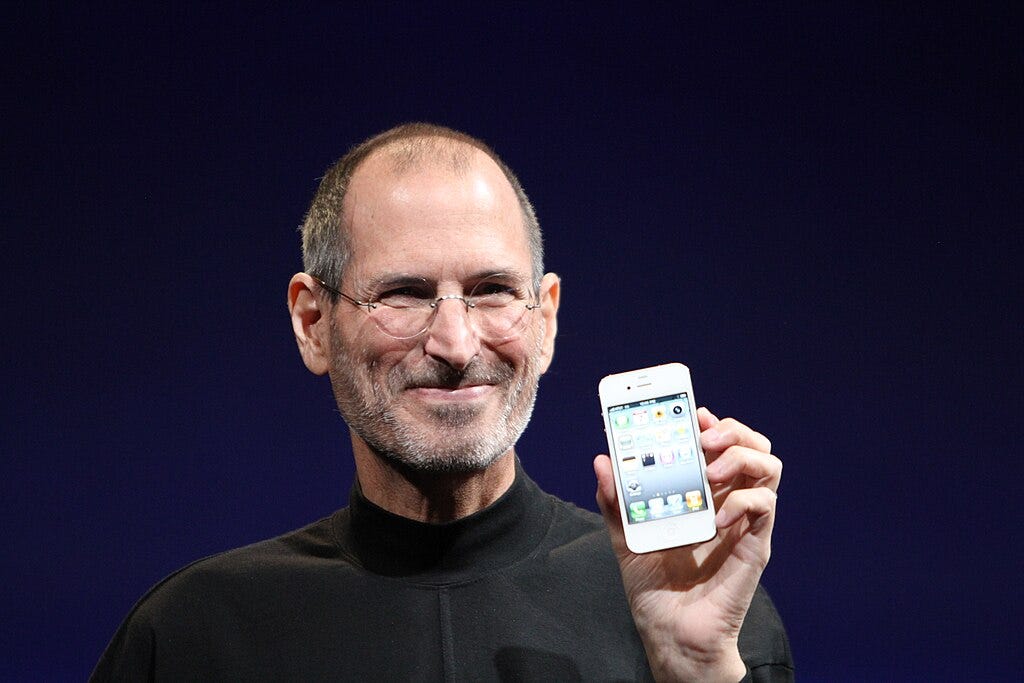

Justin Fanelli: We have the best customers imaginable, Sailors and Marines. And we have just about the most opportunity imaginable to make a difference because the baseline has historically had a lot of room for improvement. We can make huge deltas. If something is optimized already, Steve Jobs might be able to make it a little bit better, but he probably wouldn’t have been interested in that problem, right? The alternative is something that is ripe for change. We have a lot of those big opportunities across national security. Demand side opportunities are rich, and people will take our calls and connect. We’re getting in the dojo with a lot of new folks who have strong ideas, and we’re rumbling through and trying to make big changes. One thing that has surprised me is the number of people from different sectors and walks of life who want to help make a difference. If we can have more engagement, or if it can spread, we want that. It’s a special time; the world is feeling smaller.

A&B: How did you come to join the U.S. Navy?

Justin Fanelli: My career has felt a little like Tarzan swinging from vines. In my case, it’s swinging from interesting challenge to interesting challenge. This country has been really good to me. I went to school for electrical engineering; the Air Force picked that. I had taken science courses but nothing with a circuit in it, so that was a leap. I don’t know if I would have landed on EE without the military. Sometimes I tell people I would have chosen marketing or advertising, because I like the storytelling aspect of the work so much. But EE has been a dream of a jet stream to ride as hardware changed in the midst of some of the most fun years of Moore’s Law. Software started eating the world and I found myself in one of the best positions possible to choose my own adventure. Only in hindsight do I realize how fortunate I was to swing from hardware to software and back and for lessons from both to compound on each other along the way. Panning out to figure out how the dots connected was periodic, at best. But almost always — even if it was at the last minute — there was one or a couple of different lines to pull on.

A&B: Tell me about a couple of those rope swings.

Justin Fanelli: I’ve been in and out of the Department of Navy and I’ve been lucky to always be working on more than one hard problem, more than one vine, at a time. It has made day-to-day experiences more vivid. Connections have come faster and “vaster” this way; like reading more than one book at once. They interact in an intriguing way. It tends to feel richer, fuller. I was working in healthcare before this set of jobs. It was still national security — defense health. One trigger that rattled in my brain from years before was Robert Gates saying, Health care is possibly the biggest long term threat to national security and how it was “eating the U.S. military alive.” I interpreted that to mean that in addition to the health care of our very important troops, the increase in spending on health care was cutting majorly into opportunities to improve. If we couldn’t figure out how to slim that down, then it would cut into our ability to defend our country. Naive me, I started looking into that ten or so years ago and realized it was a crowded space but many dots weren’t connected. Some work was being done in a narrow way, but I couldn’t find proof that the needle was moving in the right direction on the whole. And so, I started to explore, read, and talk to soldiers, doctors, data scientists. I realized that I already cared about the population within the DoD and that it fit well with mission-driven thinking. The heterogeneity of this population was peak compared to other population sets in this country. It was a data gold mine for solving problems that could help the country as a whole. I was hesitant to jump towards that vine. But once I did, it was an immersive several years.

A&B: Do you see other spaces where technology that wouldn’t historically have been called important to the national security apparatus is now paramount?

Justin Fanelli: The U.S. has a pretty great track record on innovation. Today, government funding and partnerships move the needle profoundly. The Department of Defense, National Science Foundation, and NIH are wildly underrated. Turns out these are springboards for every sector in practice. Those three basic research arms have benefitted every person and every business vertical. Very early public-private partnerships have launched into innovations that we barely recognize by the time they make it back to us as beneficiaries in usable form. The national security apparatus specifically has acted like a launchpad for emerging technology more so than just a sector; we have strong data on this.

Justin Fanelli: Now, who’s doing the work? Since the Vannevar Bush days, it happens through government pushing on government, academia, and commercial labs. When you’re doing basic research or applied research, there may be some original intention, but exploring and discovering can open new doors. So you’re a scientist, starting with domain knowledge, then through learning by doing, applying it, mixing, mining, fracking, and figuring out applications that anyone can use. This beautiful, imperfect process has been responsible for more breakthroughs in the last hundred years than any other time in human history.

A&B: Is the government as funder of deep technologies changing?

Justin Fanelli: Being a better kickstarter and investor, I think so. The activity has been there for a long time. So many externalities have changed that I think in hindsight we can look back and enumerate a few sizable shifts. In general, we might be at the beginning of a value renaissance. We have more momentum right now than most realize. Excitement around the CHIPS and Science Act, the IRA, and space is booming. Wins coming out of these areas could have compounding effects, propelling and unifying effects that build on one another. Telling better stories in the public-private partnership space is right up there with those wins. We leave so much untold that it prevents momentum from building up. The private sector is better at reporting wins than the public sector and public-private because it has had to be. I believe the renaissance sits on the other side of a few more wins and better public-private storytelling. If we get that right, then government can shift from playing not to lose to playing to win more often. In my portfolios our social circuitry has shifted to pushing past false tradeoffs and prioritizing outcomes and it’s better for everyone involved. It’s better for the private sector and free market. It’s better for employees. It’s better for consumers. The esprit de corps is contagious. I don’t see a lot of downside to us leaning harder in this direction. As evidence builds up, what we can expect out of public-private partnership is rising.

A&B: Tell us about some of those wins.

Justin Fanelli: A common historical example to explain the point. When the iPhone exploded, almost everything in it had government-funded research running through it. There are a dozen components with their own subsystems that are amazing. There are comedy bits about this; every little subsystem and sub-subsystem is incredible. But what that actually looks like is a lot of unrelated teams working together. In this particular case, several parts of larger industrial bases, improving components, synthesizing them, and then connecting it all into a whole product. That’s a model that everyone knows and experiences; now multiply that by almost every sector and we can walk through current and hopefully upcoming breakthroughs.

Justin Fanelli: Now let’s talk about a current application. One ongoing win is the increasing resilience of key infrastructure systems and networks. Failover, contingency, and continuity of operations that we have architectured together and/or leveraged are leaps and bounds ahead of where we were a few years ago. When a system or set of systems goes down, we have more options, Many of them not requiring manual action anymore and significantly less downtime. What they say is, if you don’t have a plan ready when the window of opportunity opens, you’re likely waiting for the next window. In this particular case, my groups really took this to heart and are now operating more like gardeners than carpenters. Scouting innovation adoption opportunities rather than trying to build them ourselves.

A&B: Give us an example.

Justin Fanelli: Compute and connectivity at the edge. We were stuck on old technologies, it wasn’t keeping pace, and we were missing big opportunities. With more methods, players, and data, we unlocked better outcomes for a bunch of different interdependent communities. Another example is adaptability across the board. This applies both domestically and abroad. Our ability to make changes in hours or minutes instead of what used to be weeks, months, or even years is more important and more available than before.

A&B: What is on your wish list at the Navy?

Justin Fanelli: People first. People who love to work are more fun to work with and better at their jobs — either at the beginning or in time. It’s certainly a matter of fit. But there are people who you can call and they say, “Here are my constraints, limitations” and then there are others who just want to learn and want to work and want to get better. That chasm is a distinction that I just never want to underestimate again in my life. People are a power law difference, leapfrogging vs plodding along. Number two is team players and that open mindedness. This isn't just another attribute of those drivers we will add these together. But the idea of an open mind over an ego is critical. The best comedians are philosophers. I saw Jerry Seinfeld once talk about how to raise his kids and he said humility was the number one trait to pass on — to keep that open mind. It didn't stick when my dad told me that, but I’m obsessed now.

A&B: What do those open-minded drivers need to be great at?

Justin Fanelli: That keeps changing. That answer right now is different from what it’ll be in the future and it’s different from what it was in the past. The best model I've seen is just “versatilists,” which means that these are people who have at least two specialties. You’re taking bets when you specialize. I specialized in two things in undergrad and one of them was semiconductors. Some people said, “Almost no one works in this. It’s a very small field.” But I liked it, kept with it, and it has benefited me a lot even though I was probably never going to work it directly. Point is specialization does more for us than we see right away, if it’s part of a portfolio approach and paired with the generalization piece. As people say, optimists rule the world, because if you're negative, then you’re right, that’s stop energy. We want to be rational but optimism and being around other optimists just provides this kind of elastic fuel.

A&B: When you get them in the building, is this what you preach?

Justin Fanelli: What’s the line from the Bible: Preach the gospel at all times and if necessary, use words. There is a need for internal and external communication but if you’re around the right people, high standards are contagious and it seeps into your intuition. And then the social circuitry just really builds on itself. We’re all learning so much faster than if we were apart or closed off. It’s almost like interstitial compounding. If you play jazz music together all day, you learn more in a few months than you would in a year of mission.

A&B: What’s on your technology wish list?

Justin Fanelli: Tech that brings the biggest impact. The simple technology that scales to answer a hard problem is the best answer to many questions. And the frustrating part where I think people get stuck or annoyed, is they say, “You asked for an appliance, we provided it, why couldn't you use it?” Well, if the onus is on the buyer to translate technology into a need, and there are more sellers than buyers, then it’s just a mismatch. We want to make that easier and clearer, and there are a couple of different ways that we can unleash the people who not just have the ideas, but have that tenacity to bring the improved outcomes to fruition.

A&B: Do you think Silicon Valley is investing in the right things?

Justin Fanelli: There’s incredible innovation happening in Silicon Valley and from early stage folks all over the country. Are they building the right things? Let's get really aspirational. If we said yes, then what would we be looking forward to? So I think we’re doing pretty well. But we’d always like to see more efficiency and competitive advantage. Innovation has happened when folks pursue both their dreams and extraordinary, “wow” outcomes. We're talking about protecting peace, we're talking about deterrence, actively wanting the world to be a safer place. I hope that we can always keep getting better. And maybe different focuses happen in different states and they build on each other. Decentralized innovation will grow. That doesn't feel like it’s a problem that you close out. It’s an infinite problem that you continue to get much, much better at if you’re trying very hard.

A&B: Do you get the sense that there’s a movement in Silicon Valley rising around peace, national security, and so on — or maybe we can call it a renaissance?

Justin Fanelli: This generation cares a ton about purpose. It’s a socially minded generation. I’d have trouble speaking in detail as to how well the problem has been framed for different groups. Does national security mean peace? Well, I can tell you when the commander of INDOPACOM speaks, he is so vehemently in favor of deterrence and having the world be a safer place that it moves you. I think people who engage in listening to those voices think it’s easier to connect. The idea of the mission orientation, I see that picking up some steam in different ways. I haven’t seen trends, but in the classes that I teach at Georgetown, we have more people who are both entrepreneurial and looking for service to be a component of what they’re doing than ever before. And when I interact with Stanford students I think the same is true. This resurgence could be a way to unleash more folks. Look at the energy around the first cohort of NobleReach and STEM learnings coming out of the Council on Foreign Relations community. But it always hangs in the balance of what individuals want to do. In my singular experience when people have leaned in towards service and towards something that matters, then it has facilitated further growth.

A&B: When you give advice to a young entrepreneur, where do you direct them when it comes to finding opportunity?

Justin Fanelli: Generically, intersections. I would say that where you have access to a very hard problem, and you can talk to knowledgeable people about that, is where you’ll find a lot of benefit. My favorite example is Hacking for Defense. I love teaching that course. I-Corps within the National Science Foundation is based on similar principles and is in widespread use. The beautiful part about the government is that there’s no shortage of problems. We are a vast country and we have people who are very, very focused on interesting problems who will find applications. But I think where real value lies is in having both a technical lens and a problem lens. Things to gravitate towards are places where you have access to a lot of information. It’s just like AI: if you don’t have that data, or if the data is very hard to get to, that is a friction problem. Unless you really love that problem, it is a barrier to entry that will slow you down. Where you have access to problems and experts, I would liken those to data. I would say that there’s interstitial compounding in that.

A&B: Does the term deep tech have any meaning to you?

Justin Fanelli: It grates on some people, but it doesn’t annoy me. I think it is a reframe, a reset. It suggests that we are talking about technology that is probably not SaaS, and maybe it’s frontier and not ready yet. There’s a timeline associated with deep tech and a level of sophistication that may require translation words depending on which audience you're talking to. I’d say it doesn't say much more to me other than those two things: level of depth and level of time.

A&B:. Can you talk about other rising innovation hubs outside Silicon Valley?

Justin Fanelli: Our country is vast in landmass, personalities, and tribes. It’s so rich and interesting. I don’t want to overstate the matching — Kansas takes this problem and so on — but where we are closer to specific problems and we can get a handful of people with different skill sets to circle around those problems, then we can build pillars of innovation that are specialized in a topic area. I don't know how far-fetched this is, but thinking about a constellation across the country, where we say, “Of course, you go to this hospital for this type of medicine. They’re the specialists and we can’t all be specialists in everything.” I'm not saying that we divvy this up, but if there ended up being hubs and spokes — complementary “best of breeds” — that feels like a win to me. If we have APIs of specialization, and we can light up those different dots, what can we produce for the country or the world? I think there’s more magic available to us than we even realize.

A&B: This has been great.